This blog was written by Lilith Charlet, a student of History of Art in the School of Culture and Creative Arts, University of Glasgow, 2020.

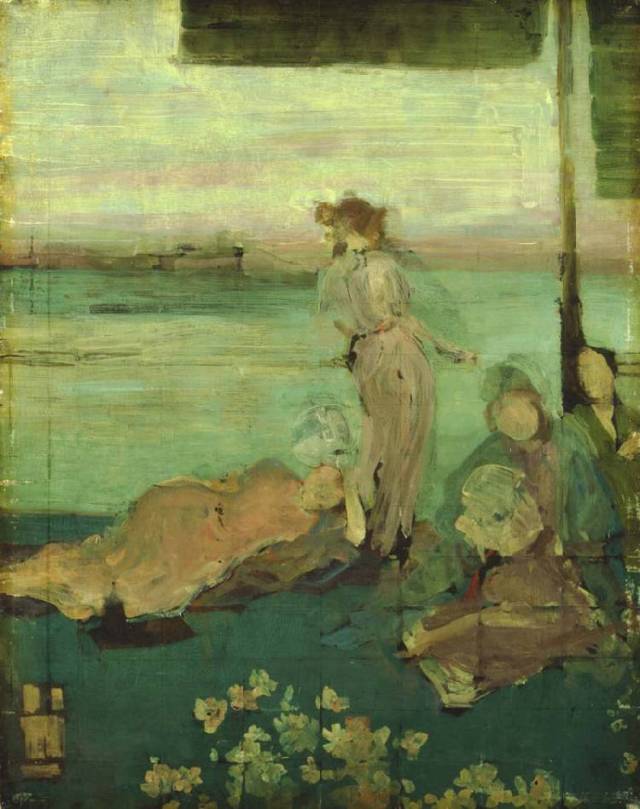

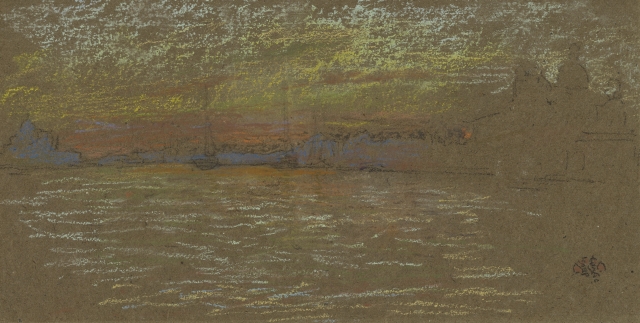

In 1879, the Fine Art Society of London commissioned Whistler to produce a set of twelve etchings in Venice. During his trip, Whistler fell in love with the Italian city and ended up staying fourteen months instead of the three allocated at first. During this period, he produced about a hundred magnificent pastels, along with the required etchings. It was not the first time he explored the medium, but his prior experiences were a lot more varied and often consisted of “quick sketches of beautiful women.”[1] Although he did draw and paint some landscapes before, he turned fully to landscape pastels in Venice. There he started to develop a profoundly unique and personal use of pastels, exploiting the brown paper as a basis for his works. As a result, his landscapes, such as The Riva – Sunset; Red and Gold (fig. 1) possess a hazy colourful atmosphere, the medium application revealing the grainy texture of the paper and integrating its colour in the composition.

Fig. 1: James Abbott McNeil Whistler, The Riva – Sunset; red and gold, 1880. Chalk and pastel on paper, 140 x 267mm. Yale University Art Gallery, 1966.9.27.

At the end of the eighteenth century, “pastel [became] increasingly denigrated in the critical literature as undemanding and feminine in contrast to the stronger, more masculine technique of oil painting.”2 Consequently, we had to wait until the second part of the nineteenth-century to see a resurgence in pastel painting.3 Whistler was part of this late nineteenth-century pastel revival and his pastel productions, especially the ones he brought home from Venice, form a major part of his work. Excited by the Venice pastels, Thomas Way wrote a letter to Whistler in May 1880 in which he expresses his concerns about the transport of such a fragile medium:

“I too, hope much from the pastels … Meanwhile (again) I have been very anxious about the careful transit of these same for I know how soon they are injured. Can you have a dozen slight deal boxes made the exact size of the paper, each to hold a limited number of the pastorals dash – with tissue between each – and no room for shaking and consequent rubbing … Thus you would be saved the risk of there being over hauled on the homeward journey.”4

For anyone who has ever used this medium, the issue of fixating, conserving and transporting pastels will be obvious. Their fragility, beautifully described by Diderot as “the precious powder … which falls off as easily as scales from a butterfly’s wings,”5 poses an obvious challenge to their adequate preservation. Museum visitors usually admire exhibited works of art, without always knowing the impressive efforts of museum staff working in the shadow to put up such an exhibition. This includes for instance the participation of curators, conservators, museum educators, tour guides, marketing teams and so on. With this post, I would like to highlight the technical aspect of conserving pastels such as Whistler’s. Without this crucial work, the public would not be able to enjoy the beauty of these artworks. To do so, I interviewed Professor Joyce H Townsend, Senior Conservation Scientist at the Tate and Honorary Professor of History of Art at Glasgow University, about the challenge of preserving such fragile pieces of art.6

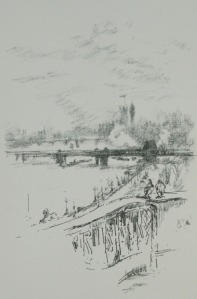

Fig. 2: James Abbott McNeill Whistler, The Old Bridge – Winter, 1879. Chalk and pastel on paper, 191 x 259 mm. The Hunterian, University of Glasgow, GLAHA 46080.

The Hunterian Museum owns four of Whistler’s Venice pastels: The Old Bridge – Winter (fig. 2), Nocturne: ships and gondolas, Venice (fig. 3), Sunset; red and gold – Salute (fig. 4) and Salute – Sundown (fig. 5). Before getting to the exhibition space, these pastels would have to be transported from their usual storerooms (Kelvinhall in the case of Glasgow University’s Hunterian’s collections). This transport is one of the major issue when caring for pastel paintings. When I visited the collections in Kelvinhall to see these four pastels, it was the first thing the conservator mentioned. She recounted, laughing, how stressful it had been when they had to transport them. With the powdered texture so easily detaching from the paper, pastels are more delicate to transport than other types of works. Professor Townsend explained to me that they would usually be transported “flat or with the case at 45 degrees from flat.” However, damage is not only caused by the work’s position. Indeed, the vibration caused by the road, even when buffered with adequate transport boxes and rugs, still damages the paintings.7 Leila Sauvage, Bill Wei and Marcias Martinez recently researched a way to predict how much vibrations a pastel can take before being extensively damaged.8 Interestingly, they discovered that “damage in pastel paintings due to vibration is cumulative.”9 This implies that a painting has a certain ‘quota’ of travels before “damage becomes unacceptable.”10

Fig. 3: James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Nocturne: ships and gondolas, Venice, 1880. Chalk and pastel on paper, 200 x 299 mm. The Hunterian, University of Glasgow, GLAHA 46082.

It is interesting, from a theoretical point of view, because it reveals the tension between exhibition and conservation, maybe more than with other mediums. We do want to show these works, and museums today insist on the importance of the transmission of knowledge. It is then crucial for these works to be exhibited and accessible to the public. At the same time, the more they will move, the more they will be damaged, and we also want to protect them from further deterioration. They have an important role to play in future historical research and they will allow historians to gain a better understanding of our past. It seems like a complex paradox. Museums work within that space, within that tension between transmission and conservation, and strive at finding the right balance – but it is not always an easy task.

Fig. 4: James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Sunset; red and gold – Salute, 1880. Chalk and pastel on paper, 202 x 300 mm. The Hunterian, University of Glasgow, GLAHA 46084.

When speaking about the difficulties of transporting pastels, Professor Townsend also explained that “museums used to tape glass in frames to hold it in case of breakage when it travelled, but the taping and tape removal [could] generate static and cause immediate damage.” She explored this issue in depth in 1993 with Heather Norville-Day and Timothy Green.11 At the time, they needed to transport some of Degas’s pastels for an exhibition. To prevent static charges and further deterioration of the works, they decided to use glass glazing and to tape it to “limit damage should breakage occur.”12 This choice, made to protect the work, actually led to the development of static charges that attracted the fragile pastel powder to the glazing. This demonstrates how delicate these artworks are and how complicated their manipulation is. Any small detail, as specific as taping, could be decisive in protecting or harming the work.

Fig. 5: James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Salute – Sundown, 1880. Chalk and pastel on paper, 202 x 268 mm. The Hunterian, University of Glasgow, GLAHA 46083.

The conservator’s work is constantly made of such crucial choices. For Professor Townsend, “if the pastel is in good condition and in its original frame, the decision whether to unframe it is the hardest one of all, because the frame provides such important and rare historical evidence.” For artists, however, the choice seems to rely more on whether or not to use a fixative on their pastels. Historically, “framing pastels paintings behind a protective sheet of glass remained [until the mid-eighteenth century] the recommended way to preserve the fragile image.”13 When the interest shifted from glass to fixatives, multiple engineers and inventors of the eighteenth century, including for instance La Tour and Loriot in France, claimed to have found the easiest and most efficient way to fic the medium. “One challenge was identifying a suitable substance; another was finding an appropriate method of application.”14 Until recently, sprays did not exist. Hence many different techniques were used: floating on the surface of water, blowing through a straw or sprinkling with a brush.15 Very different from today’s chemical fixatives, artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth century would have used alcohol, fish glue, egg white or Arabic gum.16 Applying a fixative is an irreversible process, which explains why conservators and artists are usually weary of it; it is indeed difficult to predict how it will impact the aspect of the painting and how it will age.

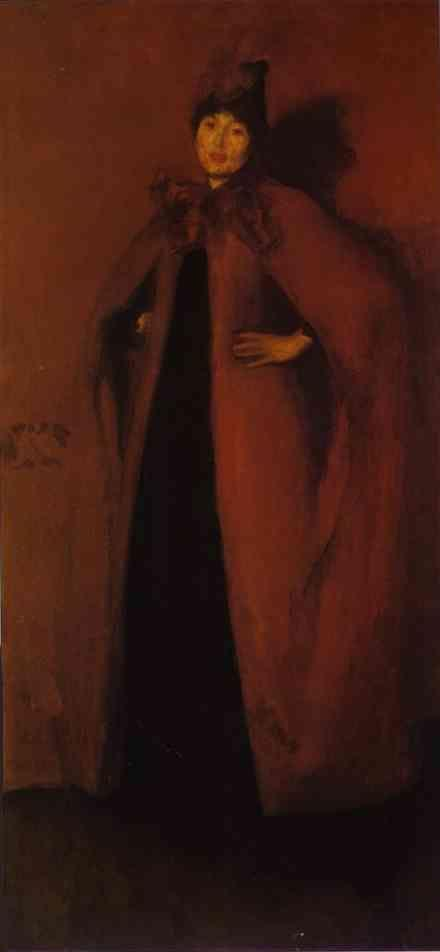

According to Professor Townsend’s observations, Whistler’s pastels at the Hunterian Museum do not seem fixed. Sunset; red and gold – Salute (fig. 4), however, appears to be covered it a multitude of darker spots. In an informal discussion, one of the Hunterian conservator and Professor Margaret MacDonald explained that this might have been the result of a sprayed application of a fixative in the past. The impact it had on the work (which still remains absolutely stunning) emphasises how important such decisions can be. Not only can fixatives have massive repercussions on the works, but even analysing them is greatly complicated by the fact that it any sampling is excessively delicate.17 On the other hand, Sauvage, Wei and Martinez’s research suggests that fixatives might improve pastel paintings’ resistance to transport vibrations.18 Although they do insist “that this does not imply that one should use a fixative to protect pastel paintings from vibrations,”19 it shows how much more there is to learn about the use of fixatives. In short, “at present … conservators simply do not have sufficient information to make a judgement – positive or negative – regarding the effectiveness of fixatives.”20

In this blog post, I hope to have highlighted the complex position of conservators, especially when confronted with works as fragile as Whistler’s pastels. The difficult choices they have to make often touch upon wider philosophical questions – is preservation more important than exhibition? Can (and should) we always fight against the influence of time? How much can we modify a work for the sake of its conservation? Pastels in particular, because of their extreme fragility, push conservation to its limits, reaffirming the importance of such issues. Moreover, conservation is located at the intersection of chemistry, engineering and art history; it blurs the limit between traditionally divided fields. Usually restricted to the collections storerooms and laboratories, it unfortunately remains far from the lay public, even when so much is at stake in the shadow of exhibitions.

NOTES:

[1] Robert H. Getscher, James Abbott McNeill Whistler: pastels (New York: George Braziller, 1991), 22.

[2] Thea Burns, The Invention of Pastel Painting (London: Archetype Publications Ltd., 2007), 153.

[3] Freya Spoor, “Revival of pastel in late nineteenth-century Britain: the transience of a modern medium” (PhD diss., University of Edinburgh, 2017).

[4] Letter from Thomas Way to Whistler, The Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler (online), https://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/correspondence, GUW 06082, accessed April 13, 2020.

[5] Denis Diderot, Diderot on Art, ed. and trans. J. Goodman, vol. 1 (New Haven: Yale University Pres, 1995), 77.

[6] This discussion dated from February 24, 2020.

[7] Marion F Mecklenburg, Art in Transit: Studies in the transport of paintings, 1st edn (Washington and London: National Gallery of Art, 1991).

[8] Leila Sauvage, W. (Bill) Wei and Marcias Martinez, “When Conservation Meets Engineering: Predicting the Damaging Effects of Vibrations on Pastel Paintings,” Studies in Conservation, vol.63, sup 1 (2018): 418-420.

[9] Ibid. 420.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Heather Norville-Day, Joyce H Townsend and Timothy Greer, “Degas pastels: Problems with transport and examination and analysis of materials,” The Conservator, vol. 17, no. 1 (1993): 46-55.

[12] Ibid. 47.

[13] Burns, The Invention, 145.

[14] Burns, The Invention, 149.

[15] Margaret Holben Ellis, “The Shifting Function of Artists’ Fixatives,” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, vol. 35, no. 3 (Autumn-Winter, 1996): 242.

[16] Information obtained through correspondence with Professor Townsend, Holben Ellis, “Artists’ Fixatives” and Burn, The Invention.

[17] Information obtained through correspondence with Professor Townsend.

[18] Heather Norville-Day et al., “When Conservation Meets Engineering,” 419.

[19] Ibid. 420.

[20] Holben Ellis, “Artists’ Fixatives,” 251.

Claude Monet, La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume), 1876. Oil on canvas, 231.8 x 142.3 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Claude Monet, La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume), 1876. Oil on canvas, 231.8 x 142.3 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.